This article contains sensitive content about traumatic experiences that may be distressing to some readers

The third year of Canada Post’s annual Truth and Reconciliation Stamp series focuses on artwork by Survivors of residential schools.

The stamp images shed light on the history and legacy of Canada’s residential school system, with artwork expressing personal experience, resilience, Indigenous culture, and hope for a better future for all children.

To create the stamps, Canada Post again partnered with the Survivors Circle of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, who selected artists Robert Burke, Helen Iguptak and Adrian Stimson.

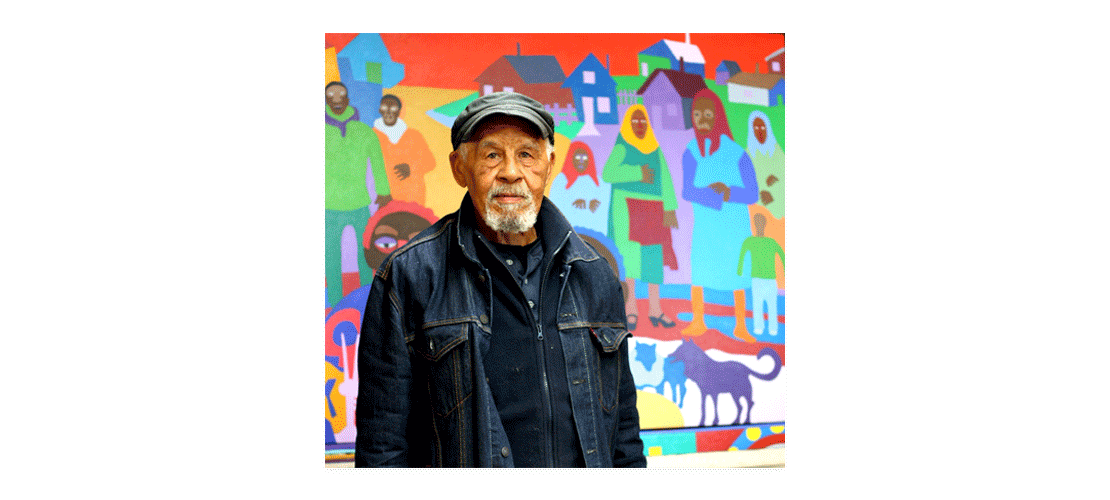

Robert Burke

Born in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories, Robert Burke is the son of a Black American soldier and a local Métis woman. His paintings are often visual memories of St. Joseph’s residential school in Fort Resolution, Northwest Territories, where he was sent at age 4. Far from his home and family, he says his memories from that time are not happy ones.

Image credit: Anahita Ranjbar

Burke decided to go to art school in his 50s, after a decades-long career in forestry and as a heavy machinery operator and mechanic. He had held a lifelong interest in art. Burke says he started to understand in third year of art school that painting can act as a voice and began working in a style that reflected his own stories and experiences.

“Once I realized that, I sort of went through a mental change. I realized that painting art in a Western style wasn’t exactly what my voice was all about. You know, I’m an Aboriginal. I’m from the Northwest Territories,” Burke says.

His paintings use simple forms, bright colours and contrast to express stories about Burke’s experiences and his Black Indigenous identity. It was his grandmother’s story that inspired him to explore his Indigenous ancestry in his art.

She lost Indigenous title after her father received “scrip,” a federally-issued document redeemable for either land or money. This historically stripped generations of Métis of their Indigenous title in Western Canada.

He recalls summers as a child, when he left school and was sent out on his own. “They used to kick you out of residential school in the summertime. You’d get on the Sant Anna [a mission boat], and you’d go across the Great Slave Lake, up Slave River to Fort Smith. Then they’d turn you loose. I had nowhere to go. I was a homeless child, so I used to sleep in the RCMP barracks,” he says.

“I had that whole element of homelessness as a child, which became part of my paintings once that connection opened up. That element, that silence, becomes very bright and light.”

Burke has received several grants and recognition for his art. An exhibit of his paintings was mounted at Fort Smith’s Northern Life Museum & Cultural Centre in June 2015 and at Yellowknife’s Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre the following year.

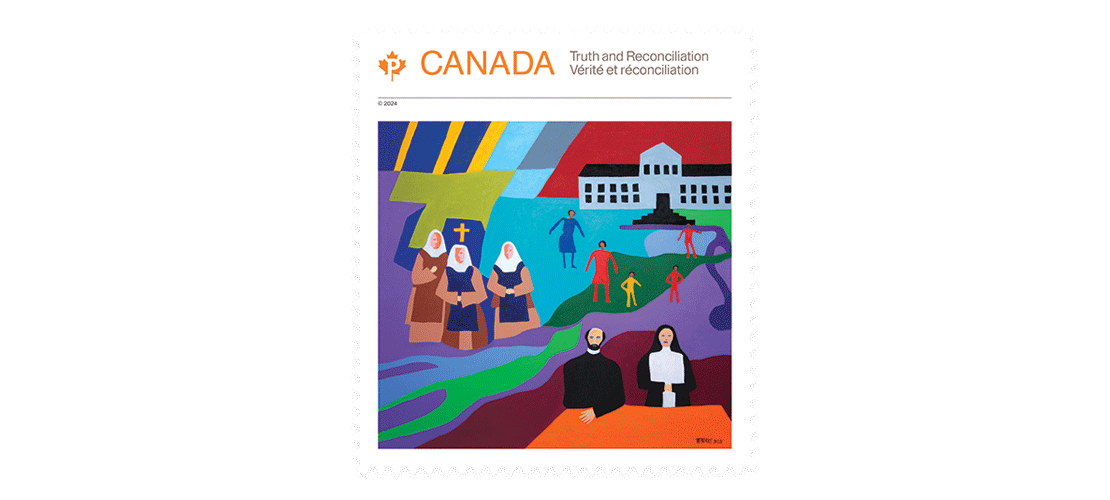

Helen Iguptak

Helen Iguptak recalls the time she was taken away from her home in what is now Nunavut, at age 7, to live at Turquetil Hall residential school in Chesterfield Inlet. She was taken by boat and remembers the feeling of trading her warm caribou clothing for store-bought cotton clothes.

Image credit: Angela Hill/CBC Licensing

“I noticed it was kind of windy and the wind was going right through my clothes. I started thinking, how am I going to survive this winter,” Iguptak told CBC in an interview in 2018.

Iguptak today carries on Kivalliq dollmaking – a centuries-old Inuit tradition from the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut.

She took up the artform in the 1990s. But Iguptak learned to make her first doll at residential school. She befriended an older girl who taught her how to make the “little friends” that comforted her and helped protect her culture from being taken away.

“When I was in Chesterfield I had one friend who taught me how to make a doll, so I made one under her instruction. She taught me how to make basic clothing,” she told CBC. “I was only like 7. Just before I finished it – I think I was putting the hair on – I ran out of thread and I was too scared to ask for thread. I looked around the floor and saw something black, so I used that to finish the doll. It was a human hair.”

When she eventually left Chesterfield to go home, she says she was so excited she completely forgot about her doll.

Today, Iguptak is recognized as an artist helping to protect Inuit culture and continue the doll tradition. Her dolls are intricately stitched to capture the details of Inuit traditional dress. Details in her work typically include caribou-skin clothing, kamiks (sealskin boots) and colourful beadwork. They’ve been displayed in galleries and exhibitions across Canada.

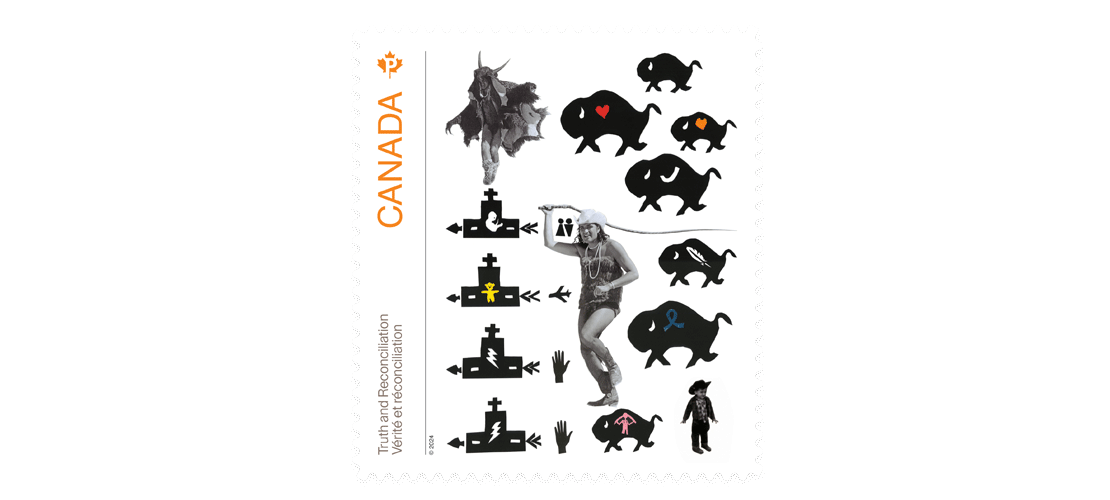

Adrian Stimson

Two-Spirit interdisciplinary artist Adrian Stimson is a member of the Siksika Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Alberta. He attended three different residential schools in his youth – experiences that have influenced artworks speaking to genocide, loss and resilience.

Image credit: Blaire Russell

Stimson uses symbols that are a hybridization of popularized conceptions of “the Indian,” the cowboy, the shaman and Two-Spirit being. His performance art has depicted recurring personas like “Buffalo Boy” and “The Shaman Exterminator.”

“These characters really sort of speak to my research and history around the colonial project,” he says, with meaning that plays on both humor and tragedy. “It’s a game that plays back and forth, which is something I’m very interested in as an artist.”

Stimson’s stamp artwork conveys themes of abuse, resilience and the power of reclaiming his culture. It includes an image of a feather, what he says is for all residential school Survivors “who didn’t have a voice, who died and lived without telling their stories. It’s those ancestors who I feel I have a responsibility to, to help bring their stories to light.” It also includes a picture of himself as a child, representing the start of abuse at residential schools.

Bison are another common symbol in his works. Partly representing resilience for the Blackfoot people, he says their story of survival is analogous to the story of Indigenous Peoples. His stamp image includes seven Bison, a reference to the seven generations it takes to slowly move through the process of healing and reconciliation.

Stimson has exhibited and performed in major galleries and museums across Canada and internationally. Among other recognition, he received a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2018 and a Hnatyshyn Foundation REVEAL Indigenous Art Award in 2017.

He hopes his artwork opens space for people to learn more about Canada’s history and better understand the experiences of Indigenous Peoples.

Stimson emphasizes his gratitude to the Survivors Circle for guiding the stamp process. “It was really a wonderful opportunity to have those discussions with people who share the very same experiences,” he says. “I’m eternally grateful to them for the care they gave me, but also the encouragement to tell this story.”

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line provides 24-hour support to former residential school students and their families. If you require support, please call 1-866-925-4419.

New stamps highlight artwork by residential school Survivors

Available now