Canada has long been a world leader in aviation technologies and innovation. Canadians bravely took to the skies when airplane flight was in its infancy and also contributed significantly to advancements that allowed our country’s reputation for innovation to soar.

The achievements of aviation and aeronautical trailblazers are commemorated in Canada Post’s latest stamp issue, Canadians in Flight, a series that began in 2019. The new stamps showcase the historic contributions of a groundbreaking female pilot, a legendary bush plane and three aviation innovators.

Violet (Vi) Milstead

As a teenager, Violet (Vi) Milstead (1919-2014) watched a small plane buzz the field during a high school football game. At that moment, she knew she wanted to be a pilot.

“Flying, as a vocation, is in a class by itself,” she later told Shirley Render, author of No Place for a Lady: The Story of Canadian Women Pilots, 1928-1992. “It affords satisfactions – intangible ones – available in no other line of work.”

Born and raised in Toronto, Ont., Milstead was taken out of school at age 15 to help in her mother’s wool shop during the Great Depression. Her mind set on flying, she set about saving for lessons. She took her first on September 4, 1939.

Seven months later, Milstead had earned her private and commercial pilot’s licences and, soon after, her instructor’s rating. She worked as a flying instructor at Barker Field in Toronto, until aviation fuel became rationed during the Second World War.

In 1943, Milstead sailed to England to join Britain’s Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a civilian organization that ferried military aircraft between factories and front-line squadrons. ATA pilots – including 168 women – weren’t eligible for military service because of a disability, their age or other restriction.

“For women to fly military aircraft was extremely revolutionary,” said Joyce Spring in the documentary Women of WWII: Spitfires in the rhododendrons.

One of very few Canadian-born women in the ATA, Milstead flew 47 types of aircraft, including single-engine fighters and multi-engine bombers. She logged more than 600 hours of flight in Spitfires, Mosquitos, Beaufighters, Hawker Tempests, Hellcats and other aircraft and became the ATA’s longest-serving Canadian female pilot.

ATA pilots delivered 147 different types of aircraft, each of which fell into one of six categories or classifications. Pilots were trained on planes in each class, starting with single-engine planes and progressing to single-engine fighters, then multi-engine aircraft. Pilots carried a booklet with key information about all planes in each class but sometimes flew ones they had not previously flown.

At five feet, two inches tall, Milstead sometimes had to sit on a packaged parachute, or her black leather overnight bag, to see out the windows of some of the aircraft. Auxiliary pilots also flew without using radios, in case they might be overheard, so Milstead and others navigated by dead reckoning and with maps and compasses.

In 1945, Milstead returned to Canada and instructed at Barker Field, where she met Arnold Warren, whom she later married. In 1947, the couple moved to Sudbury to work at Nickel Belt Airways, where they flew as bush pilots and taught people to fly.

Milstead was one of Canada’s first female bush pilots and transported miners, lumbermen, hunters and fishermen and others while keeping an eye out for forest fires.

“Vi was an inspiration to any young woman because of her ability to fit into a male world and retain a sort of femininity,” said novelist Jane Urquhart, a distant relation. “She never paused for a moment to think that she couldn’t do it.”

A Member of the Order of Canada, Milstead was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame and received the Amelia Earhart Medal, among other honours.

de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver

Named one of Canada’s top 10 engineering achievements of the 20th century, the DHC-2 Beaver is considered the best bush plane ever built. Its short take-off and landing capability – as well as flexibility to be fitted with wheels, floats or skis – made it ideal for accessing and connecting remote regions and communities of the country.

Near the end of the Second World War, de Havilland Canada began work on a rugged and reliable replacement for the wood and fabric-covered aircraft that had previously helped open northern Canada.

The company consulted with the Ontario Provincial Air Service and bush pilots, including First World War flying ace and pioneering bush pilot C.H. “Punch” Dickins. (Dickins was commemorated with a stamp in the inaugural edition of Canadians in Flight.) Their recommendations from a questionnaire were incorporated into the design.

The result was an all-metal, single-engine, high-wing, propeller-driven plane, which could carry up to nine passengers or bulk cargo. It was dubbed a “half-ton flying pickup truck” by de Havilland Canada managing director Phillip Garratt.

The Beaver made its first flight on August 16, 1947. Before production ended in 1968, de Havilland Canada had produced a total of 1,692 Beavers (including 60 powered by turbines), delivered to 62 countries.

The aircraft has been flown all over the world, from Algonquin Provincial Park lakes to New Zealand farm fields, from Africa to the Andes and the Arctic to the Antarctic, where a lake, an island and two glaciers were named after its significant service in the area. Many were also used in the Korean War by the United States military.

Still in use today, the Beaver has been employed in forestry patrol, water-bombing, aerial photography, aerial fish stocking, crop dusting and cargo delivery.

Kenneth Patrick and the CAE flight simulator

Seventy-five years ago, former Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) officer Kenneth Patrick (1915-2002) of Saint John, N.B., founded CAE Inc. (then known as Canadian Aviation Electronics Ltd.). His goal was to “create something Canadian and take advantage of a war-trained team that was extremely innovative and very technology-intensive.”

The company started operations by repairing, overhauling and installing ground communication equipment and antenna farms in the Arctic for the RCAF. In 1952, CAE secured its first contract to develop and build a flight simulator – a self-contained training unit that replicated an aircraft’s cockpit and all potential situations and conditions pilots face – for the RCAF’s CF-100. The project developed and tested new techniques and methods, which improved the accuracy of the simulator.

In 1954, the company had grown from 18 employees working in a vacant aircraft hanger in Saint-Hubert, Que., to a workforce of 500 in a new facility adjacent to Montréal’s Dorval Airport. The following year, CAE was hired to design the first Canadian-built flight simulator for the DC-6B for Canadian Pacific Airlines.

By 1962, CAE had entered the field of digital technology to pursue a larger share of the commercial market. This shift led to revolutionary advances in visual systems and motion technology.

In the 1970s, CAE continued its expansion and received orders for helicopter and power plant training simulators and even mechanized postal equipment for Canada Post. The company was also selected to design a simulator to replicate the functionality of the Canadarm and to train astronauts on its controls for NASA’s space shuttle in 1976.

By the early 1980s, CAE had developed a simulator so realistic it was no longer necessary for all flight training to be completed on actual aircraft. And, in 1983, it became the first company to deliver a simulator before the aircraft itself, a Boeing 757, had been certified.

Today, air travel is the safest mode of transportation in part because commercial pilots train in simulators – most produced by CAE, a global leader in training in civil aviation, defence, security and healthcare.

W. Rupert Turnbull and the variable pitch propeller

W. Rupert Turnbull (1870-1954) was a pioneering aeronautical engineer who developed a device that improved the performance of a plane significantly – while working in a converted barn in Rothesay, N.B., a suburb of Saint John, where he was born.

Turnbull graduated with a mechanical engineering degree from Cornell University in 1893, and did post-graduate work in physics at the University of Berlin. He then worked at the Edison Lamp Works in New Jersey for six years before returning to New Brunswick, where he established his own laboratory and engineering consultancy.

In 1902, Turnbull built the first wind tunnel in Canada and conducted research on the stability of aircraft and airfoils. He also experimented with lift devices, internal combustion engines, turbines and hydroplanes over the next decade. He published valuable insights in aeronautical journals in the United States and Britain.

During the First World War, Turnbull assisted aircraft manufacturers in England and began to work on a mechanism to control pitch during flight. Several years later, he had developed his most notable invention, the variable pitch propeller, which allowed pilots to easily adjust the pitch, or angle, of propeller blades in flight – the equivalent of changing gears in a car.

The device improved the aircraft’s efficiency, since the propeller pitch best suited for take-off or climbing differs from that needed for cruising at different altitudes. Patented in 1922, it was successfully ground and flight tested at Camp Borden in Ontario. The patent rights were later sold to the Curtiss-Wright Corporation in the United States, which produced thousands of propellers based on Turnbull’s design.

For his achievements in aviation, Turnbull received many honours, including the bronze medal from the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain and, in 1977, was inducted posthumously into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame.

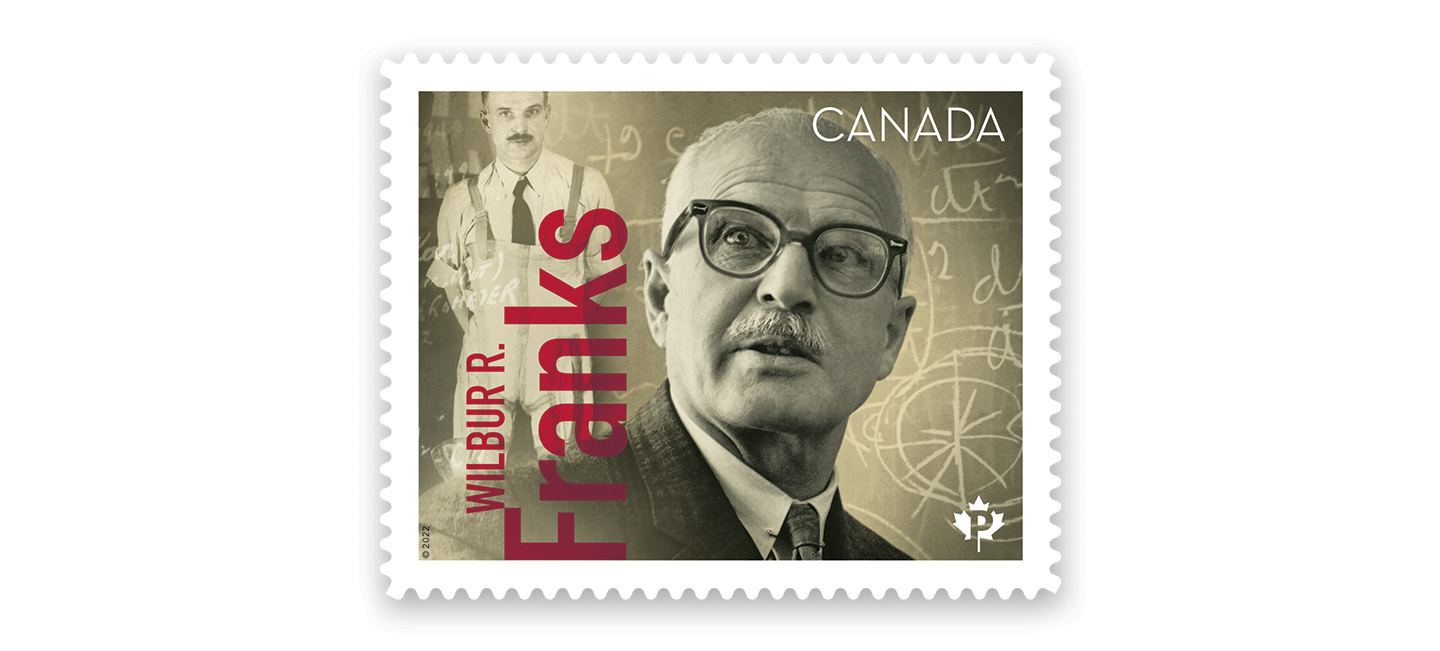

Wilbur R. Franks and the G-suit

Born in Weston, Ont., Dr. Wilbur Rounding Franks (1901-86) developed the world’s first anti-gravity suit used in combat during the Second World War, as well as Canada’s first human centrifuge to test it.

He was at the University of Toronto in 1939 when he was asked to join Dr. Frederick Banting’s aviation medicine research team. The Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps had directed the team to study the life-threatening risks associated with high-speed aerial manoeuvres. Pilots were losing consciousness due to strong gravitational (G) forces, which were preventing the heart from pumping enough blood to the brain.

Having previously prevented test tubes from shattering in centrifuges by inserting them into larger tubes filled with water, Franks developed a rubber flying suit lined with water-filled pockets. The resulting hydrostatic pressure successfully countered the G-forces.

The suit, which was also called the Franks Flying Suit, was first used during the invasion of North Africa in 1942. Today, the basic elements of his design are still in use by air force pilots, cosmonauts and astronauts around the world.

For his pioneering work in aerospace medicine, Franks was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and awarded the United States Armed Forces’ Legion of Merit. He also received two awards from the Aerospace Medical Association. In 1983, he was inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame.

The Canadian Society of Aviation Medicine created the Wilbur R. Franks Award, and the Canadian Forces School of Survival and Aeromedical Training in Winnipeg is dedicated to his memory.

Canadians in Flight stamps honour aviation and aeronautic pioneers

Available now