Jillian Lynch remembers Valentine’s Day 2014 clearly. Her younger brother Myles shuffled from his bedroom to hers. The short walk exhausted him, but he often made the trek with his IV pole and oxygen tank. “Myles asked me to make him blueberry pancakes,” says Jillian, “then he collapsed.” Myles was 16, and cystic fibrosis was ravishing his lungs.

Over the next five years, Myles had three successful double-lung transplants, the first Canadian to do so. “Organ donation gives the ability to truly maximize life,” says Jillian, 26. “It literally brings life, but also a new perspective on life.” For Myles, that new perspective drove him to set new goals after every surgery. “Because of organ donation, Myles got to go all the way.”

Register to become a donor

Visit organtissuedonation.caToday, more than 4,400 Canadians are waiting for a life-saving organ and many more for healthy tissue to recover from a potentially fatal illness. A single organ donor can save up to eight lives.

Myles Lynch and his sister Jillian.

Myles was airlifted to The Hospital for Sick Children (Sick Kids) in Toronto and Jillian drove there with their parents from their home outside Cornwall, Ont.

Myles was put on the list for a lung transplant and a match came nine months later. “He was glowing the day of his surgery, he was so excited,” says Jillian. “Myles was so ready to receive a second chance at life.” The surgery took more than six hours, and Myles’ recovery took several weeks. “Then he went all out,” says Jillian.

First up: swimming. “He could hold his breath for the first time in years and seeing him come out of the water and breathe normally was amazing,” says Jillian. Myles also went longboarding, biking and hiking. In the summer of 2015, he was a torchbearer in the Pan Am Games torch relay. A crowd cheered as he ran 200 metres along a Toronto street and carried the torch into Sick Kids. “He told me ‘This is the best I’ve felt in my whole entire life,’” remembers Jillian. But after two years, Myles’ body rejected his new organs. He needed another double-lung transplant.

“Since we were kids, Myles used to say ‘Jillian, every day is a bonus day.’” – Jillian Lynch

Myles waited three months for new lungs. Again, he recovered quickly, then jumped into life. He wrote music and recorded songs that streamed on Spotify. He visited elementary and high schools speaking about cystic fibrosis and the importance of organ donation. There was a “boys’ trip” to Boston with a cousin, where Myles explored Harvard University and “some of the best pizza shops in the city,” says Jillian.

This time Myles got two and a half years. At age 23, his body rejected his lungs again.

“Myles looked at the last transplant as his world record, this was his Olympics,” says Jillian. He devoted himself to recovering and building strength because he had a new goal: to get his driver’s licence and hit the road, alone, from Ontario to British Columbia.

He documented the seven-week trip for his YouTube channel and for his movie, 8 Thousand Myles, which had three screenings in his hometown.

Myles made time for advocacy, helping to collect more than 1,300 signatures for a petition asking the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health to study a national opt-out program for organ and tissue donation.

“Myles went through a lot in a very short life,” says Jillian. “But he said to me ‘Make sure people remember me for the good things and see me as more than just a person with CF who received numerous transplants. I’m an adventurous guy. I’m a public speaker. I’m a songwriter. I’m someone who can do a lot in a very short amount of time.’”

Myles Lynch died on New Year’s Eve 2021. He was 24.

Addison’s story

It was a normal pregnancy and an uneventful birth. Elaine Yong delivered a seven-pound girl and, with her husband Aaron McArthur, became a parent for the first time. Life was good. Three weeks later, it was a nightmare.

That day, Baby Addison was listless and cranky, and she wouldn’t eat. “Then her lips started looking a little blue,” says Elaine.

The parents drove from their Vancouver home to the nearest emergency department. Doctors suspected an infection. Addison might need antibiotics and an overnight stay, but that hospital couldn’t admit children. At the children’s hospital 20 minutes away, “things went down hill fast.”

Addison was barely moving; doctors poked and prodded, but she stayed silent. When they attached her to an echocardiogram to evaluate her heart, “the air in the room changed,” remembers Elaine.

The baby’s heart wasn’t pumping blood. Without life support, she would die.

Doctors hustled Elaine and Aaron out of the way and raced Addison to the pediatric intensive care unit where she was put on life support. “The machine is terrifying,” says Elaine.

Hours later, the parents saw their baby in a pediatric medical crib. There was a tube in her neck, a tiny mask and hose over her face, electrodes on her chest, and needles under her skin. “It’s beyond your worst nightmare,” says Elaine.

A diagnosis came two days later: Left ventricular non-compaction.

In utero, the heart starts as spongy tissue and gradually compacts into the firm muscle required to pump blood. With Addison’s condition, that compaction never happens. The heart remains spongy and weak, and, in the most severe cases, without a heart transplant, the baby will die.

Four days after being admitted to hospital, Addison was on the transplant list. Three days after that, the surgeon called Elaine and said, “I have a Mother’s Day gift for you.” A tiny heart was available.

After a nine-hour surgery, early on Mother’s Day 2011, the new heart was inside Addison, but it wouldn’t beat. Addison went back on life support, and a few days later doctors tried again. “It started beating and it’s been going like gangbusters ever since,” says Elaine.

Today, 11-year-old Addison McArthur attends Triathlon Camp and Ski School.

Addison is a voracious reader, and she hikes and kayaks with her parents and younger sister, Charlie. Her health is stable, and she has plans for her future. “At first I wanted to be a pizza maker and an astronaut,” she says. “Now I want to be in engineering and science.”

“Transplant is not a cure,” says Elaine. “You’re exchanging a life-threatening, life-ending condition for a chronic condition.” Addison will take immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of her life, so her body doesn’t reject her heart. She’ll always take precautions to avoid infections, which could be fatal.

This “new normal” means the family lives in the moment. “Let’s not wait for later,” says Elaine. “Whatever opportunities we have, let’s take advantage of them now.”

“We wouldn’t be a family without this incredible gift of organ donation. The ‘we’ as we know it wouldn’t exist.” – Elaine Yong

Addison McArthur (front) with her parents and sister.

Every year, the Yong-McArthurs celebrate Addison’s “heartiversary” – the day of her transplant surgery. They also recognize the birthday of her donor, Audrey, who was one week old when she died. “We plant flowers every April 30 to honour Angel Audrey,” says Elaine.

The Yong-McArthur family are all registered organ donors. “Children need organs too. As a parent, that’s a hard thing to think about,” says Elaine. “But if this is important to you, take two minutes now and register.”

Jan’s story

Jan Clemis knew for decades that she would need a kidney transplant. Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) runs in her large family. Her grandmother, father, sister and various cousins all inherited the incurable condition. Jan was diagnosed with PKD at age 22.

The disease causes cysts to grow in the kidneys. They damage the tissue and can cause the organ to fail completely. Doctors told Jan she’d go into renal failure by age 45; she made it to 59. “My kidneys were so big I looked like I was nine-and-a-half months pregnant,” she says.

Cysts had made her kidneys swell. Her body couldn’t filter waste and toxins, which can also stress the heart. Weak and sick, Jan was hospitalized for 10 weeks. When she was finally stabilized, both kidneys had to be removed. “Kidney patients are fortunate though, because we have the option of dialysis.” Jan did that for 16 months.

“Without organ donors, we can’t have a future.” – Jan Clemis

Every other day, Jan drove from her home in Taber, Alta., to a hospital in Lethbridge and sat connected to a dialysis machine for four hours, before driving back home. It was exhausting. “I was very lucky,” she says. That kind of travel is impossible for many in rural Canada. “Some try home dialysis, some opt for conservative care, which means they take no treatment,” says Jan.

After her surgery, Jan joined the waiting list for a donor kidney. Her youngest child was spared PKD and volunteered to be tested to see if he could donate. “I said, ‘What about your sisters? They’ll need a kidney one day too,’” remembers Jan. All her children agreed she was the priority. It’s a memory that makes Jan cry.

The testing process took months, but Blair, 30, was a match. Mother and son went into surgery in August 2018. Three months later, Blair was back to work as a chef full-time. Jan felt great in days and was fully recovered in six months “with a green light to return to working and swimming!”

“Organ donation gives the best outcome for a full life, and that’s what I’ve regained,” Jan says. “I’m not tied to a machine anymore. There are no restrictions with my diet, I can eat a banana or an avocado or drink a big glass of water. I’m so grateful.”

Jan had been a Foods and Nutrition school teacher in Oregon, Montana and Alberta for 41 years and during her dialysis worked as a supply teacher. Becoming immunocompromised after the transplant meant she had to leave teaching altogether. But retirement has meant more time with family, especially her four young grandchildren. “I just want to get in all the grandma snuggles I can.”

On average, a transplanted kidney from a living donor stays healthy and functioning for 25 years. That would put Jan around 85. “I know this is just borrowed time, this is all just bonus days,” she says. “To have a rich, unencumbered life has been a blessing for me.”

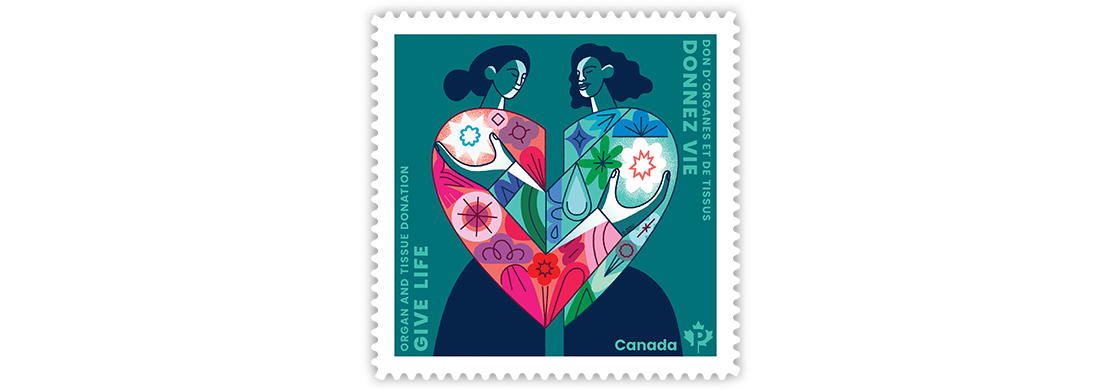

Stamp brings awareness to need for organ and tissue donors in Canada

Available now